To filmmaker Dawn Porter, the "Eyes on the Prize" message is plain: "We cannot wait for the savior"

The first two parts of Henry Hampton’s landmark series “Eyes on the Prize” are a methodical accounting of the birth and early strides of the Civil Rights Movement. Part I aired in 1987 and walked through the seminal events between 1954 and 1965 that launched the struggle.

Part II followed the icons of the movement, including Malcolm X, Muhammed Ali and Martin Luther King, Jr., as well as looking at the efforts of the Poor People’s Campaign, the Black Panthers and Fred Hampton’s role and assassination – figures and groups that have since been chronicled in scripted films and many documentaries.

Hampton, who died in 1998, is not here to see the series’ stellar third installment, for which filmmaker Dawn Porter took up the charge as its executive producer. But he would have approved of its assiduous dedication to the humanity of America’s ongoing struggle to gain the rights that a second Donald Trump administration is reminding us that we can’t take for granted.

If you are feeling unmoored and powerless, "Eyes on the Prize III: We Who Believe in Freedom Cannot Rest 1977-2015” is a potent prescriptive, and extremely timely. The six-part series speaks to the power of regular people banding together in whatever way they can to create massive resistance to injustice.

Work on this series began in 2021, a reasonable timeline for an anthology covering nearly four decades of civil rights struggle. That needs to be said given its uncanny timeliness. Those unfamiliar with the production scope of an anthology like this should be forgiven for assuming the producers and filmmakers were inspired by recent headlines. Instead, they looked farther back to find the stories that inform where Americans find themselves now.

The first episode, “America, Don’t Look Away 1977-1988,” addresses the fight for fair housing and healthcare. These are present concerns, but Geeta Gandbhir’s film chronicles the battles everyday residents fought in the late ‘70s through the ‘80s to simply live safely and with dignity.

"What I was looking for were examples of all the myriad ways that oppression happens. And it's not always obvious,” Porter says.

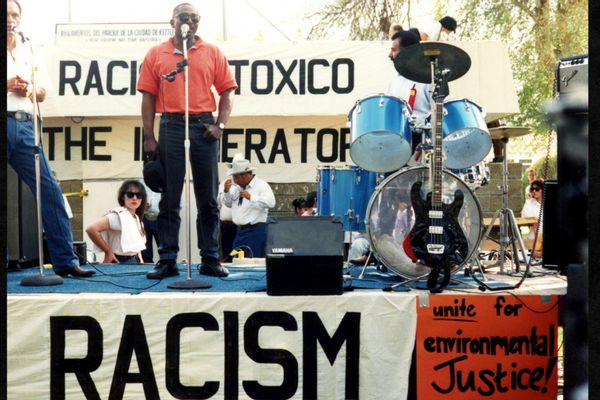

Episode 4, Rudy Valdez’s “Spoil the Vine 1982-2011,” speaks to residents of Black communities in West Virginia and Florida that were exposed to deadly toxins from a Union Carbide factory and an Environmental Protection Agency dump site, placed mere feet from their homes.

In “Trapped: 1989-1995,” Samantha Knowles looks at the ways over-policing in Washington D.C. and South Central Los Angeles criminalized the poorest of the poor, especially Black men. The Smriti Mundhra-directed “We Don’t See Color” zooms in on affirmative action at both the university level and in one North Carolina community’s public school system.

“What I was looking for were examples of all the myriad ways that oppression happens. And it's not always obvious,” Porter explained in our recent conversation. “The housing story in the Bronx? That is not an obvious story. The environmental racism that occurs? That is not an obvious story.”

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

We spoke with Porter about that emphasis, and what she hopes audiences will take away from these new "Eyes on the Prize" installments.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

When did you first decide to revisit “Eyes on the Prize”?

I was actually really hesitant to do it. And I was hesitant because it is such an important story, and it was a little daunting. The original “Eyes” has been historically taught in schools. It is something that the country rallied around. And so the significance of this next installment was so apparent.

In the end, it was too important an opportunity to pass up. So we started working on this in 2021. We were still in lockdown . . . It took several months to pull together this team, and in the conversations with HBO and the producers, the very first thing I asked for was, “We need to have six different directors of color, six different teams.” It was a big ask, and HBO completely understood why I wanted to have all of these creatives involved. That honors Henry Hampton's original structure.

Also for modern times, it makes the point that we have all these brilliant directors, and their contributions are integral to the collective whole of this series.

Let's talk about that because I think that when I look back — and it's been a very long time, I'll admit, since I've seen the full 14-hour “Eyes on the Prize” — I remember it being a family affair. It was a big deal in my household. I don't know if it was the same for you.

One hundred percent. That was part of my worry about that, like, oh my goodness — this is something I sat down and watched with my family. With my mother, with my sister, with my grandparents, my cousins. It was a big deal. It was like watching “Roots.”

The approach this time matches the era in terms of how we talk about democracy and the ways that it's under attack. One that’s very apparent now is the idea that a fully multicultural, [socioeconomically diverse] and united populace would be a main force in bringing all of these rights that were fought for and are continuing to be fought for, into fruition and to get them fully solidified.

Can you talk about how that is reflected in the directors that you sought, and the subjects you spoke with and featured?

Yes, and that framing is really critical to what we were trying to accomplish and what we had in mind as we were assembling these teams and selecting these stories.

In the 1960s we had a very easily identifiable enemy. There were laws saying, “You cannot sit here, you cannot eat here, you cannot go to school.” In the 1970s and '80s, '90s and early 2000s, and even today — well, I'll get to today – but in the period that we cover, racism and exclusion were not quite so obvious, and it was important to us to point out that while laws had been eradicated or changed, behaviors had not always been eradicated or changed. And so our job was a little harder. We had to point to things that were more subtle forms of discrimination and exclusion. Those were the stories that we were looking for.

I would say that 2025 is now becoming more like 1968, where there are specific and not subtle attacks on full equality for all people, regardless of background. When Trump has weaponized the term diversity as something that corporations, educational institutions and even PBS are stepping back from, that is outrageous. That is 1968-level discrimination.

"We had to point to things that were more subtle forms of discrimination and exclusion. Those were the stories that we were looking for."

So what we are pointing to in this series of “Eyes” are the more subtle forms of systemic discrimination. . . . So we were quite intentional in choosing the people to tell the stories. I wanted to have directors who were from minority backgrounds, and so we have a range of people, but also people who have different styles. Having those different opinions and not being afraid to let them lean into how they wanted to do their storytelling was really important.

But then we needed to be cohesive, and so the very first thing I did was have everybody gather, and we all watched the original series together, all the episodes. We sat in a room and watched them all together, and then we had a conversation about what we saw. How did "Eyes" become so powerful? What was it about the storytelling that was so impactful? Were we going to have a narrator? If we were going to have a narrator, who would that voice be? You know, Julian Bond was the narrator for the first eyes. Were we going to do that?

And we decided not, for many reasons, but having those collective conversations about what we as a unit were trying to accomplish with this installment, those were really, really important conversations.

Still from "Eyes On The Prize III" (Courtesy of HBO)

Still from "Eyes On The Prize III" (Courtesy of HBO)

I'm glad you pointed out that there isn't a narrator because, for me, that choice highlighted a cohesive theme. The theme I noticed—perhaps influenced by the dominant conversation right now—is the power of community.

Was that intentional? Did that theme emerge as you and the directors watched these together, or am I seeing it because it's such a prevalent topic at the moment?

No, it's completely intentional, although I will say we were making this in 2021. So we could not know how relevant it would be in 2025.

I certainly respect the choice to have a narrator in the original series. But what I feel as a filmmaker . . . what a narrator does is have you feel like there is one answer to a problem, [that] there is one definitive take.

I think there are many ways to resist, but I think the most powerful part of our story is that it is coming from these individual people. There are some moments where the people who are just doing the things that they need to do realize that they can do it. And I think that is very powerful right now.

"We were making this in 2021. So we could not know how relevant it would be in 2025."

You know, I made a film about John Lewis. I had the pleasure of traveling with him for a year, and that was during Trump I. And I would say to him, while we were traveling, “Mr. Lewis, I'm so worried about kids in cages.” “I'm so worried about” … XYZ thing. And he would say, “There's always something that you can do.”

Not everyone is going to protest in the streets, but that doesn't mean you're not resisting. That doesn't mean you're not paying attention. So figure out what it is that you can do. It might just be being kind to your neighbor. It might be resisting the idea that we are so separate and apart. It may be pushing back against that false narrative. One of the things that we wanted to come through here is that ordinary people, they just start doing things. And that is what form the resistance ultimately takes.

We cannot wait for the savior. The savior is us.

The original “Eyes on the Prize" aired on PBS. It was publicly available. You can still find it online. This is airing on HBO, a cable premium service. I’m wondering, thinking in terms of getting this exposed to as many people as possible, what occurs to you as an executive producer, regarding how available this will be.

You know, it's a good question. If I'm being really honest, HBO is a really great place for this. They put in the resources to have six different teams with six different producers of color. They are going to publicize this. I wish to goodness gracious that PBS were in a position to do that.

… So one of the things we have to be is practical. Would I rather have this series exist? Yes, that is the answer; yes, it will exist. And I have no doubt that the HBO executives, who have been insanely supportive of this effort, will figure out ways to make it as available as it should be.

…And I love PBS. I've done a number of projects for PBS, and I know the struggles that they have. They're in danger of being defunded. The President of the United States and his minions have called for eliminating public television. That's the situation we're in right now. We need to make these stories available where they can be.

Still from "Eyes On The Prize III" (Courtesy of HBO)I want to also say about the PBS issue that I think we should be asking ourselves why our public television system is not in a strong enough position to relaunch “Eyes.” What have we done as a community to fail PBS, that they don't have the resources they need, and they're in more danger than ever? I hope this makes people realize what we will lose if we lose public television.

Still from "Eyes On The Prize III" (Courtesy of HBO)I want to also say about the PBS issue that I think we should be asking ourselves why our public television system is not in a strong enough position to relaunch “Eyes.” What have we done as a community to fail PBS, that they don't have the resources they need, and they're in more danger than ever? I hope this makes people realize what we will lose if we lose public television.

Whenever we think about the Civil Rights Movement, there’s a tendency—one the right wing has exploited—to treat it as a distant, settled history, defined by gigantic icons like Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, and Malcolm X, with no one stepping up to continue their legacy. What do you hope people will take away from this new iteration of "Eyes on the Prize?"

This is such an important question, and I want to address this: “Eyes on the Prize” focused on ordinary people. They did not focus on the famous people of the movement. When we look back and we see John Lewis, well, he's famous now. He wasn’t famous then. He was another student activist.

And so we cannot let people who would rather we erase this history define it, because that's when it becomes the history that you can ignore. Instead, the message of “Eyes,” then and now, is that there is not one movement leader or the leader. It's all of us who are working collectively in a communal way. That is where the power comes from. And so you cannot kill one person and stop a movement. Those are tragedies, but civil rights activism did not stop in 1968. It continues to this day.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

I spoke with Raoul Peck for one of his recent documentaries and at the end of our conversation, I asked him if he had a sense of hope. He said, “I don’t think like that. I'm not working for hope. I'm working because I have no choice” — which, you know, fair, given everything that's going on.

I want to pose the same to you because you've produced a span of content about culture and social change. And I wonder, with your work, do you have any kind of hope and or optimism in terms of the way this country is moving?

Raoul is a very good friend . . . And one of the many, many things that I admire and love about his work is his honesty. Although he may not feel hopeful, his work makes us feel hopeful because he leans into the experience of individuals, and in his beautiful telling of these stories, he gives us inspiration.

And so I would say I have had the real pleasure of doing a variety of stories. And I think what underpins all of them is this idea that people are stronger than they think. They are more interesting than they think, and they are more inspirational than they think.

. . .You know, we need to be in the dark for a little bit to remember our strength. And it's not fun being in the dark. It is not pleasant. I would rather we were not in this terrible situation. But I do not think that the worst of us will prevail. I just do not believe that. And so as unpleasant as it is, we will persevere.

"Eyes on the Prize III: We Who Believe in Freedom Cannot Rest 1977-2015" airs over three consecutive nights: Episodes 1 and 2 air back to back beginning at 9 p.m. Tuesday, Feb. 25, with Episodes 3 and 4 airing Wednesday, Feb. 26 and Episodes 5 and 6 airing Thursday, Feb. 27 on HBO. All six episodes will be available to stream Tuesday, Feb. 25 on Max.

salon